Bassai Dai opens with a leap into a cross stance, backfist, and an open hand guarding block.

Bypassing an opponent’s lead guard, or oncoming strike, the immediate application we derive from this opening sequence has the technician take control of the opponent’s head and neck. What happens next rather depends on the situation. If absolutely necessary, we manipulate the opponent, crankshafting him around, and then propel his head like a basketball into the floor. Though it will not bounce. Much.

If we are surrounded by multiple opponents, we can instead accelerate the opponent’s head hard laterally into an object or structure, or catapult it straight into opponents who think they’re standing safely out of range.

Variations around the theme are equally brutal and unpleasant – for him.

If you’ve seen this application in my recent book, Breaking Through: The Secrets of Bassai Dai Kata, we have Hanshi Bruce Clayton to thank for all the fun.

No, this application is not stolen from Hanshi Clayton’s popular book, Shotokan’s Secret: The Hidden Truth Behind Karate’s Fighting Origins. But Dr. Clayton may still be held accountable. Shotokan’s Secret encouraged me to investigate the human condition of those early Karate pioneers, the combat scenarios they prepared for, the purpose of their various kata, and the absolute need for applications to be explosive.

Breaking Through, the title of my book, calls to the translation of Bassai as “breaking down the fortress” or “breaking out of the fortress.” As a spoiler, Shotokan’s Secret hypothesizes that Bassai was a team-based bodyguarding system, and along with several other kata, was central to the extraction of the royal family of Okinawa in times of threat.

Breaking Through is also thus titled because it required a huge shift in perspective on my part and no small effort to crack the secrets hidden in traditional source material.

I believe Breaking Through is the first book of its kind as it’s a book on kata application written by a Taekwondo teacher. Bassai Dai is, of course, a well-known Okinawan pattern, a precursor system to several modern hard-style fighting arts including Japanese Karate and traditional Taekwondo. So more than one lineage lays claim to it in their syllabus.

While modern systems often emphasize the differences between styles, my ongoing research leads me to believe that practitioners prior to the 20th century frequently sought cross training opportunities from other systems. This meant that prior to the 1900s old school practitioners who braved the difficulties and dangers of travel could study a mix of Northern and Southern Shaolin arts, Okinawan Te, Japanese Koryu arts, and precursors of modern Muay Thai.

When South Korean Grandmaster Jhoon Rhee brought his system of training to the Southwest United States in the mid-1950s, what he taught wasn’t yet called Tae Kwon Do. It was Tang Soo Do, a literal translation of Karate as The Way of the China Hand, China Hand being a reference to the original name of Japanese Karate.

Tang Soo Do instructors taught Karate kata like Pyung Ahn 1-5, Tekki 1-3, Bassai Dai and Sho, Jitte, Jion, and Jiin. Grandmaster Rhee only started using the term Tae Kwon Do in 1962, though most Americans would continue to use the terms Karate and Taekwondo interchangeably. Our members then adopted the more modern Tae Kwon Do Chang Hon patterns in 1967 at the behest of General Choi Hong Hi, Founder of Taekwon-do.

Our lineage’s proximity to Japanese and Okinawan arts persisted beyond the conversion to the Chang Hon forms. When I arrived in the United States from Singapore in the early 1990s, my teachers used Chang Hon forms to put us through our paces, but black belts enjoyed an expanded curriculum, which included elements of Okinawan and Japanese patterns, aspects of Ju-Jutsu, and an Okinawan weapons-based system called Kobudo. Such was the training with AKATO, American Karate and Taekwondo Organization.

I had an early affinity for Bassai Dai and was pleased to see the appearance of the kata in Hanshi Clayton’s Shotokan’s Secret. The similarities various Chang Hon patterns shared with Bassai was a plus when I sought to use patterns as the syllabus for my training in 2005.

While I was interested to identify applications from all my patterns, the goal in 2005 was to understand the tactical worth of the traditional source material – to see the world through the eyes of the Karate pioneers. Bassai Dai, woven into the tapestry of our Chung Do Kwan lineage, was the oldest of the patterns I knew and it became a lens for me to peer back through time.

Working with Bassai Dai, we were often able to compare and contrast individual tactical phrases with the more modern forms we knew. We would deconstruct and explore technique sequences using the JDK Method. As one feature, the JDK Method applies tactics to oncoming initiatives from the same side, or from the opposite side. The best applications allow us to apply one technique to receive a strike irrespective of the opponent’s left or right side.

The JDK Method also assumes critical failure somewhere along the sequence. We always assume non-compliance. Such an obstacle forces us to search for solutions from within the pattern to create workarounds. If these workarounds are nowhere to be extrapolated in the form under consideration, we then seek inspiration further abroad, sometimes dredging through soft style concepts for the advantage we seek. This variegated approach to pattern analysis has reaped us huge rewards and led to a depth of understanding which simply had to be shared.

While the book centers on Bassai Dai kata, it isn’t solely a how-to book. I share my journey and growth from being a white belt to becoming a black belt instructor, how I found myself 10,000 miles away from the mothership and on the verge of giving up martial arts altogether. That personal journey is juxtaposed with the challenges of a fixed pattern-based training environment, the various pitfalls or opportunities the modern practitioner may experience on his or her own journey, and various ways to extract the best results from traditional source material. This is the first part of the book.

The book’s value to the Taekwondo community lies in its ability to offer a fresh perspective on traditional, or old school, training material. My fundamental training in hard style Taekwondo does not need reinvention, I myself train new students very similarly to the way I was trained when I first started. The esoteric insight I have since acquired from the likes of Bassai Dai does not shake the foundations of hard style martial arts training nor the basics taught to me by my teachers. In reality, application training as I present in the book fills out that training framework and makes it come alive.

Any talk of a written martial art resource for the Taekwondo community eventually brings up the Encyclopedia of Taekwon-do written by the art’s Founder, General Choi Hong Hi. Undeniably, the Encyclopedia is an excellent resource. It provides amazing information that helps develop and structure a worldwide martial art. To this day, there is still nothing like it. But an over-reliance on any single source of knowledge might not always facilitate one’s progression in the martial art. If practitioners are open to assessing other perspectives while still understanding and enjoying the value the Encyclopedia brings, they are richer for it. The assessment of other perspectives may validate what they already know. Or might, in fact, identify areas they do not know.

Aside from theory and fundamentals, Taekwondo practitioners focus on fast and powerful strikes, often delivered from a distance, and often demonstrating a penchant for head-high techniques or techniques which require a lot of athletic ability. Close-range fighting, trapping, stand-up grappling, and joint manipulation are not equally emphasized in training. This is where Breaking Through offers an edge, as it presents skills that can enhance hard style training.

Such skills are not simply taken from systems like Judo, Jujitsu, or Wing Chun, as is often the case. The applications in Breaking Through are drawn directly from material within the pattern set. Extrapolated, pressure tested, and drilled, they point to the prerequisite knowledge the pioneers of the patterns developed and ensconced in their kata.

I didn’t stop at the boundaries of hard style concepts, either. Hard style techniques involve linear, forceful movements designed to displace and destroy an opponent’s structure. Soft style techniques, on the other hand, emphasize the immobilization and disruption of an opponent’s structure and center of gravity. By being platform agnostic and incorporating the discussion of both hard style and soft style tactical concepts, the analysis of forms comes alive! We then get to cherry pick tactics that work well at specific distances. This is the 21st century after all. If we want to learn certain tactical elements or develop defenses when faced with such opposition, we should have the freedom to do so. Just as the early pioneers traveled in order to broaden their knowledge.

Recently, it was my honor to be invited to present at the American Karate and Taekwondo Organization (AKATO) Annual Seminar in Dallas, Texas. AKATO is the organization with which I started my journey in Traditional Taekwondo. For my seminar, I chose to show skills drawn from those older forms that are part of our Karate and Chung Do Kwan legacy.

However, these aren’t sparring skills to be used in a sport-based martial arts setting. They are incredibly deceptive, subversive, and subtle. The applications include their own self-correcting mechanisms to match the dynamic situations you’d face with a live opponent. And like my first example where the opponent’s head becomes your basketball, all come with a level of shock and awe. Some have called it magic!

The smiles and nods of appreciation from the 130 or so participants became more enthusiastic as the level of discomfort inflicted on my demonstration partner increased. This is one of the reasons I wrote this book in the first place. Black Belts want this kind of information. It might have been informative talking about where the pattern originates, but when we see it for its tactical value, when we learn to shut down an opponent, when we feel the ease at which this happens, when we acquire the ability to account for multiple opponents — demonstration trumps everything!

As I reach the conclusion of the remarkable journey to write and present Breaking Through: The Secrets of Bassai Dai Kata, my heart swells with immense pride and fulfillment. This book has been a deeply personal endeavour, driven by my passion for martial arts and my need to express a gratitude to my teachers by showing what I have learned based on their teaching. It is a testament to my growth in their system and a testament to the continuing benefits of traditional training.

I hope that Breaking Through serves as a guiding light for practitioners looking to explore the depths of their own training. It is my desire to empower martial artists with a fresh perspective, to bridge the gap between hard style and soft style techniques, to foster a deeper understanding of traditional martial arts training, and to encourage all to “break through” their own barriers in their lifelong quest for self-improvement. May this book be a source of inspiration, a catalyst for growth, and a taste of the exciting possibilities that await us on our martial arts journey.

About: Colin Wee has practiced three martial arts systems over three continents in the past 40 years. Colin was inducted into the Australasian Martial Arts Hall of Fame in 2020, and was formerly an Asst National Coach in Archery.

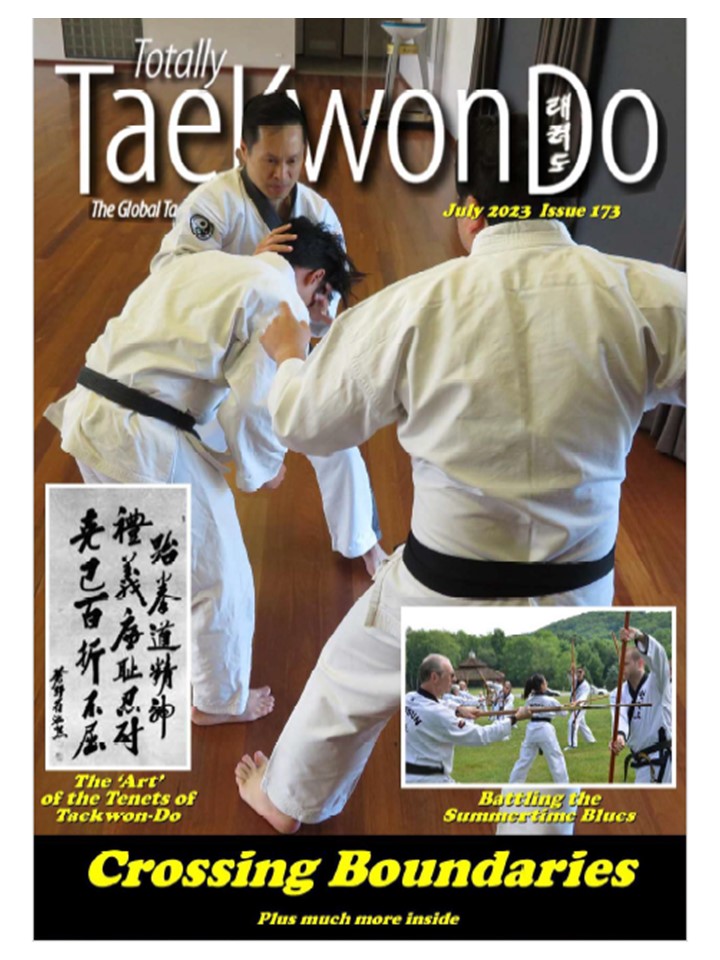

The original version of this article was submitted to and published in Totally Taekwondo Magazine July 2023 Issue 173.